SOB SISTERS:

THE IMAGE OF THE FEMALE JOURNALIST

IN POPULAR CULTURE

© Joe Saltzman and the IJPC

IJPC Experts Offer Their Top

Sob Sister Films,TV Programs and Fiction

- Joe Saltzman, director of the IJPC, USC Annenberg

- Richard R. Ness, Western Illinois University

- Howard Good, State University of New York at New Paltz

- Paul E. Schindler, Jr., the man behind www.schindler.org/movie/shtml

Contributors:

THE JOURNALISTIC SORORITY

THE SISTERS OF SIGMA OMEGA BETA (SOB)By Richard R. Ness

Richard R. Ness and IJPC 2003©

Richard R. Ness, Assistant Professor at Western Illinois University, is the author of the definitive book on journalists in film, From Headline Hunter to Superman: A Journalism Filmography (Scarecrow Press) and the only book on the director Alan Rudolph: Romance and a Crazed World (Twayne) as well as articles and reviews in the Hitchcock Annual, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, and The International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers. His current project is gender and motion picture musical scores.

As titles such as A Female Reporter (1909), The Girl Reporter (1910), and The Girl Reporter’s Big Scoop (1912) indicate, the female journalist has been a fixture of films about the press as long as her male counterparts. Even before women in the United States had earned the right to vote they were being provided with images of strong, independent, working females through films about the press. In many cases the women in these films were shown to be capable of holding their own against the men they encountered and in some cases even gained the upper hand. For example, in the 1913 film How Men Propose, by female director Lois Weber, the heroine encourages proposals from three men in succession, then reveals that she is not actually interested in marrying any of them but is only conducting research for an article she is writing on the title subject.Film viewers with at least a passing acquaintance with journalism films probably will be able toidentify such representatives of sob sisterhood as Lois Lane, Torchy Blane, Brenda Starr (although the character has had less success in films than as a comic book heroine), and the journalistic heroines of Howard Hawks’ His Girl Friday (1940), George Stevens’ Woman of the Year (1942), and Frank Capra’s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) and Meet John Doe (1940).

In the following list I have attempted to identify some less well-known female practitioners of the profession who provide interesting images of the working female journalist. I also have included a list of some of the less successful screen depictions of women in the field.

A BAKER’S DOZEN NOTABLE FILMS

FEATURING FEMALE JOURNALISTS

THE OFFICE SCANDAL (1928) – Heroine Jerry Cullen (Phyllis Haver) refers to herself as “the world’s greatest sob sister” and obviously finds nothing derogatory about that title. Jerry constantly spars with her editor over her insistence that a woman can do as good a job as a man, and finally proves the point when she demonstrates that an actress killed her husband in self-defense because he had been whipping her. In the end Jerry’s editor tells her to write the story, adding “”If you think you’re man enough,” and Jerry responds, “Say, I’ll be the head man of your sheet yet.”

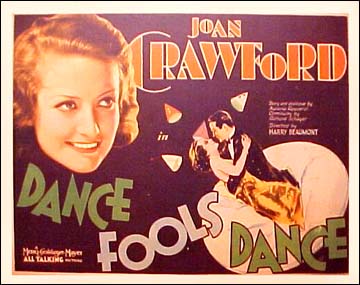

DANCE, FOOLS, DANCE (1931) – Suddenly penniless heiress Bonnie Jordan (Joan Crawford) turns down a marriage proposal in favor of getting a “man-sized job,” and eventually goes undercover to expose gangsters. While her decision to reconcile with her boyfriend and leave the paper at the end of the film might seem like a step backward, the fact that the final embrace takes place in the newsroom indicates that she at least has forced him to meet her in her territory.

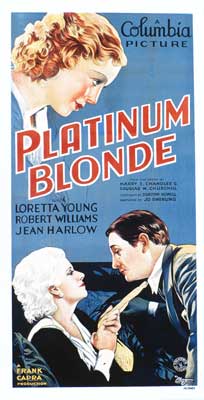

PLATINUM BLONDE (1931) -- Although not as well known as many of Frank Capra’s other films, this entertaining production anticipates a number of elements in the director’s later works, including his image of the working press. Gallagher (Loretta Young) serves as a forerunner of Babe Bennett (Jean Arthur) in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Ann Mitchell (Barbara Stanwyck) in Meet John Doe. Perhaps the highest complement Gallagher is paid in the film is that the male reporters think of her as just one of the guys (although the hero eventually comes both to recognize and to appreciate her feminine qualities).

MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM (1933) – Glenda Farrell provided a warm-up for her later Torchy Blane character in this horror melodrama. As Florence, Farrell established her image as the fast-talking, wisecracking, tough girl reporter. The character is established almost immediately, as Florence walks into the police station, slaps one of the officers on the back, and asks, “How’s your sex life?” And if Florence settles for marriage at the end, at least it’s with the down-to-earth editor, rather than the wealthy playboy.

A WOMAN REBELS (1936) – Katharine Hepburn’s Pamela Thistlewaite offers a rare image of a strong-willed female editor. Pamela rebels against the conservative policies of the women’s magazine where she works in Victorian England and begins to write pieces taking on such issues as unwed mothers, child labor, and whether a woman can have both a family and a career. The fact that the film could include considerations of illegitimate children and suicide at a time when the Production Code was in place in itself constitutes a kind of victory for women in a male-dominated social system.

WOMEN ARE TROUBLE (1936) – Ruth (Florence Rice) must battle the sexist attitudes of her editor, who believes “there’s no such thing as a female reporter.” Despite the film’s title, Ruth emerges as a more aggressive and successful journalist than her male colleagues, and ultimately represents the kind of old-fashioned reporting her editor has been demanding.

ARISE, MY LOVE (1940) – Some sources have suggested that heroine Augusta Nash (Claudette Colbert) was modeled after Hemingway’s third wife, Martha Gellhorn. Although the film fluctuates between romantic comedy and wartime drama, the character of Augusta demonstrates the growing importance of women reporters internationally and in covering events that once were the exclusive domain of male journalists.

THE TRESPASSER (1947) – This programmer crime drama is of interest for the character of Stevie Carson (Janet Martin), a recent college graduate who gets a job on the Evening Gazette. Carson represents a generation of women who gained independence as a necessity of the Second World War and has no intention of giving up a career to become a homemaker. Her independence is demonstrated when she refuses to respond after a male colleague calls her “girl” and informs him, “My name is Stevie Carson. In the future please remember that.”

THE LAWLESS (1949) – Joseph Losey’s film is interesting for its depiction of a Spanish language newspaper. Editor Sunny Garcia (Gail Russell) must battle racism in her small town, as well as the initial indifference of fellow journalist and rival editor Larry Wilder (Macdonald Carey). Eventually Larry joins the crusade and when his newspaper office is destroyed by an angry mob, Garcia joins forces with him to put out another edition.

A FACE IN THE CROWD (1957) – Radio reporter Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neal) discovers folksy philosopher Lonesome Rhodes (Andy Griffith) and makes him a media star, but gradually comes to realize she has created a megalomaniacal monster. She finally destroys him by turning on his mike after one of his programs and broadcasting his comments about his gullible public.

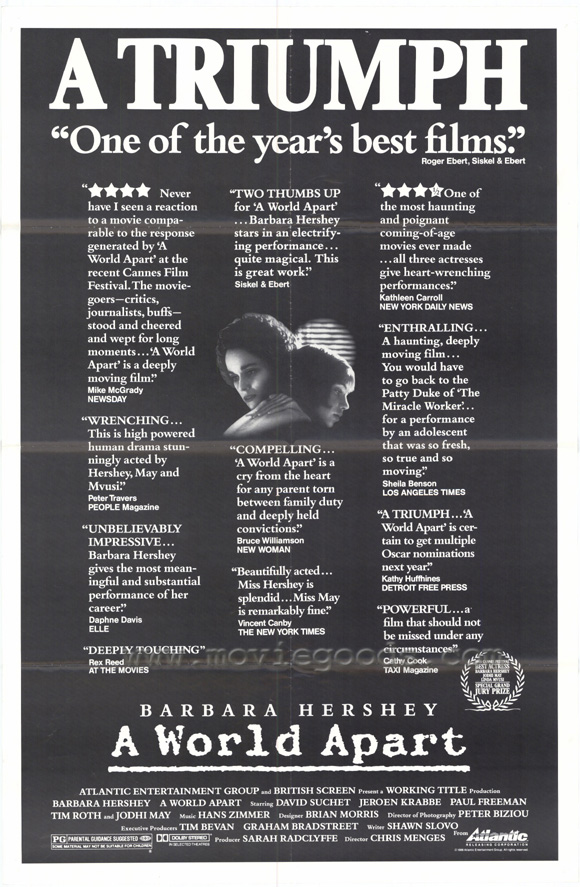

A WORLD APART (1988) – Although the profession of South African newspaper writer Diana Roth (Barbara Hershey) is only briefly addressed, much of the film concerns the imprisonment and suffering she is forced to endure because she refuses to compromise her beliefs.

HERO (1992) – Television reporter Gale Gatley (Geena Davis) questions the ethics of her own profession and the extremes to which she herself is willing to go in pursuit of ratings. The film’s attitude toward journalism is summed up in a speech Gale makes at an awards ceremony in which she compares the pursuit of a story to the peeling away of layers of an onion. While Gale seemingly aspires to something more noble, this nobility ultimately takes the somewhat questionable form of concealing the truth in favor of perpetuating a myth.

DEEP IMPACT (1998) – This action drama involving reporter Jenny Lerner (Tea Leoni) uncovering the story of a comet on a collision course with Earth earns a place in this list because in the early scenes Jenny demonstrates that one of the most important skills a journalist can have is the ability to listen. Although she initially believes she is pursuing a story on a political sex scandal, Jenny does not immediately blurt out what she thinks she knows when talking to various officials. As a result, she gradually picks up bits and pieces of additional information and begins to realize she is on to something of, well, much deeper impact.