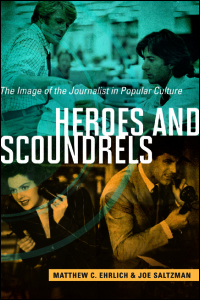

Heroes and Scoundrels:

The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

By Matthew C. Ehrlich

Professor of journalism at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

and Joe Saltzman

Professor of journalism and communication at the University of Southern California

Publication date: April 2015. University of Illinois Press

Available in hard cover, paperback, kindle (IPhone, IPad) and e-book formats)

The Heroes and Scoundrels Web site continuously updates

and adds supplementary material to the book

Heroes and Scoundrels: The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

Extended Video Introduction to

Heroes and Scoundrels: The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

Video Introduction to Heroes and Scoundrels: The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

Click here to order the video -- available to IJPC Associates only

Introduction

Why study the image of the journalist in popular culture? The main reasons are simple: First, journalism itself is supposed to provide us with the stories and information we need in order to govern ourselves. Second, journalists have been ubiquitous characters in popular culture, and those characters are likely to shape people’s impressions of the news media at least as much if not more than the actual press does. Third, popular culture is a powerful tool for thinking about what journalism is and should be.

Rather than presenting a simple chronology of depictions, this book will take a fresh approach by focusing on six thematic areas. They have been chosen because they correspond to specific fields of inquiry within journalism studies that popular culture is particularly helpful in illuminating.

The first field, history, is the focus of chapter 1. Some historians have argued that journalism history too often has served only to celebrate the press rather than providing critical insight into its problems. Pop culture regularly depicts journalism’s history through simple, linear, dramatic tales that use the past to speak to the present and that adopt partisan viewpoints on historical issues. It both mythologizes and demythologizes the press, at once celebrating and parodying well-known figures and happenings in journalism’s past. Fictional tales also can offer valuable historical evidence in their own right.

Professionalism is the subject of chapter 2. Apart from questioning whether journalists are true professionals (or even should be professionals), scholars have been particularly interested in the role of “objectivity” in journalism and in the practice and philosophy behind journalism ethics. In popular culture, so-called objective reporting is shown to be deeply problematic and is often implicitly equated to a lack of passion and commitment. Still, professional values do have a place as ethical dilemmas are brought to dramatic life and journalists who violate the public trust suffer the consequences of their misdeeds.

Chapter 3 looks at difference. Journalists have been criticized for seeing themselves as being different from everyone else—as somehow standing above and beyond the rest of the citizenry. At the same time, the struggles of journalists who are not male, white, or heterosexual have been well documented, as have the difficulties of the mainstream press in covering gender, race, and sexual orientation. In the nineteenth century and through most of the twentieth century, journalism was one of the relatively few professions in which a single, divorced, or widowed woman could find work and married women could earn enough money to take care of themselves and their families. Still, in pop culture, journalism has been portrayed as a particularly difficult career choice for women, who are caught between culture’s “gendered” expectations of them as being caring and nurturing and the gendered expectations of journalists as being tough and independent—that is, stereotypically masculine. The difficulties of ethnic minority and LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) journalists also have been depicted, with some of the most interesting portrayals having been produced by minority and/ or gay or lesbian authors or directors.

Power is the focus of chapter 4. Critics have pointed to the circumstances under which the press may violate the trust of the powerless and also how it can serve as an instrument of those who do hold political or economic power. Many popular culture works graphically depict the damage that the press can inflict on individuals, even if they might finally show journalists trying to do the right thing in the end. The negative effects of state control or censorship of the press are often dramatized, with the implication being that privately owned and commercially subsidized news media are right and just. However, pop culture also shows that corporate pressures stemming from private control can themselves lead to censorship or coercion.

If this whole book ponders journalism’s popular image, chapter 5 looks at image more specifically by focusing on the depiction of photojournalists and television journalists. Critiques of the press often warn of the dangers of manufactured image and spin, as with political events that are orchestrated for the camera. Still, others have pointed to the power of visual images to evoke empathy and emotion and appeal to the imagination, whereas many professionals and educators argue that photojournalism and TV journalism at their best serve journalism’s self-proclaimed devotion to truth and social responsibility. Popular culture dramatizes both perspectives on those journalistic professions: they can either help present a picture of the world as it really is, or they can promote lies and fluff over reality and substance.

Chapter 6 looks at war. The coverage of war has been considered one of the most important and challenging tasks for the press. Popular culture shows the journalist serving as either a necessary witness and voice of conscience in reporting on global conflict or a sensation seeker and propagandist. Much as in real life, war correspondents in popular culture must answer the questions of whose side they are on and what personal price they are willing to pay in order to report the truth.

Finally, in our conclusion we examine how popular culture has looked at the future of journalism, which itself has been hotly debated by journalism scholars. Speculative fiction points toward a press that perseveres regardless of what else may occur—useful to keep in mind as the press confronts the many challenges of today and the years to come. That is one more reason why we believe that studying the image of the journalist in popular culture is important work. Pop culture’s stories illustrate our expectations and our apprehensions regarding the press and its relationship to democracy. The task for scholars is to listen carefully to what those stories say, help decipher them for others, and remember why they matter. Ehrlich-Saltzman, Heroes and Scoundrels: The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture – pages 1, 17-18. ©University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Other Resources:

Studying the Journalist in Popular Culture - http://ijpc.uscannenberg.org/journal/index.php/ijpcjournal/article/view/79 - PDF

Fact or Fiction: Hollywood Looks at the News. An essay by Loren Ghiglione, professor of journalism, Northwestern University, and Joe Saltzman, Director of the IJPC and Associate Dean, USC Annenberg School for Communication, 2002.

The American Journalist: Fictions Versus Fact. An essay by Loren Ghiglione, Northwestern University. ©American Antiquarian Society, 1991.

Frank Capra and the Image of the Journalist in American Film, USC Literary Luncheon Speech, March 27, 2002, Doheny Memorial Library Joe Saltzman

Facts, Truth and Bad Journalists in the Movies by Matthew C. Ehrlich in Journalism, Vol. 7, No. 4, 501-519 (2006) © Sage Publications 2006.

Howard Good, The Journalist in Fiction, 1890-1930 Journalism Quarterly (Summer 1985): 187-214.

If you want to learn more about the image of the journalist on old-time radio, go to Newspaper Heroes of the Air, the definitive site on the subject.