Heroes and Scoundrels:

The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

By Matthew C. Ehrlich

Professor of journalism at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

and

Joe Saltzman

Professor of journalism and communication at the University of Southern California

Publication date: April 2015. University of Illinois Press

History

Chapter One

In this chapter we look at the image of journalism’s past that is presented by popular culture. After reviewing how pop culture treats history generally, we will focus on two eras of American press history: the early decades of modern journalism from roughly 1890 to 1940 and the so-called age of high modernism from roughly 1945 to 1980.

Popular culture employs scrupulous attention to historical detail alongside wholesale invention in shamelessly exalting figures and events that many conventional journalism histories also have celebrated. As such, it reproduces heroic myths about the press’s past.

Yet pop culture also has presented a less heroic picture at times by casting a skeptical and even mocking eye toward journalism history and by highlighting more sordid aspects that the conventional histories have sometimes downplayed or overlooked.

Ehrlich-Saltzman, Heroes and Scoundrels: The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture – pages 19-20. ©University of Illinois Press, 2015.

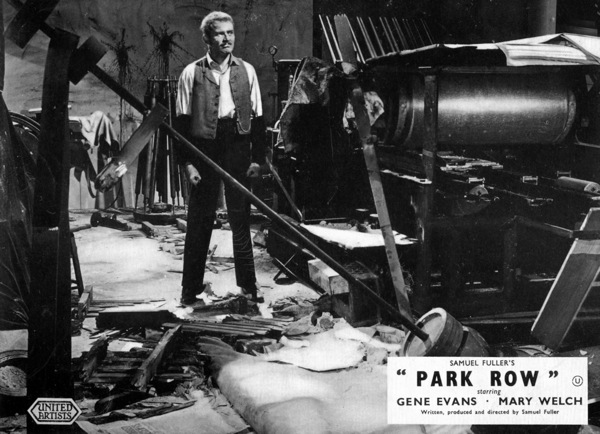

The birth of modern journalism is vividly evoked by the 1952 film Park Row, written, directed, and produced by Samuel Fuller. It stars a character named Phineas Mitchell, who founds a paper called the Globe. “News makes readers, readers make circulation, and circulation makes advertising,” he says. “Advertising means I’d print my newspaper without the support of any political machine!” The Globe leads a fund drive for the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal, prints the story of Steve Brodie’s death-defying jump from the Brooklyn Bridge, and introduces the Linotype typesetting machine via inventor Ottmar Mergenthaler. Phineas accomplishes it all despite fierce opposition from Charity Hackett, the female publisher of the rival Star, where Phineas used to work. Even though the two share a mutual lust, Phineas calls Charity a “frustrated journalistic fraud,” and her paper (without her knowledge) goes after the Globe with goons, one of whom Phineas chases down the street and pummels against a statue of Benjamin Franklin. An older member of Phineas’s staff dies amid the mayhem, but not before writing his own obituary addressed to Phineas:

Don’t let anyone ever tell you what to print. Don’t take advantage of your free press. Use it judiciously for your profession and your country. The press is good or evil according to the character of those who direct it. And the Globe is a good newspaper. I have put off dying waiting for a new voice that needs to be heard. You are that new voice, Mr. Mitchell.

Somehow it all ends happily: Charity kills the Star and joins forces with Phineas at the Globe, and the film concludes with the image of the Statue of Liberty (which, the concluding narration asserts, exists thanks to the help of a newspaper).

Park Row displays the common characteristics of popular history, including a simple, linear story and a romantic subplot, while also embodying the Whig or Progressive vision of journalism history. It is “a heroic narrative of newsmongers and muckrakers, of Davids slaying Goliaths,” of a newly responsible press (supported not by the state or political parties but by free enterprise) promoting life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, with contemporary papers implicitly carrying on the noble legacy of Phineas Mitchell. Of course, Phineas never actually existed. Still, Samuel Fuller drew on real-life models in creating a character designed “to combine all the great newspaper editors of the period” (that is, the “white male” editors of “metropolitan dailies” who “championed truth and justice for the people”).

Ehrlich-Saltzman, Heroes and Scoundrels: The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture – pages 22-23. ©University of Illinois Press, 201

A Dispatch from Reuters (1940) depicts the nineteenth-century development of the Reuters international wire service with a resounding credo: “A censored press is the tool of a corrupt minority. A free press is the symbol of a free people. For truth is freedom. And without truth, there can be only slavery and degradation!” Paul Julius Reuter passionately believes that access to information should be a universal right, and he seeks to better the world through the quick transmission of news. When he is the first to report in Europe that Abraham Lincoln has been assassinated, no one believes the horrific news. Reuter is labeled a “contemptible liar” who has ruined lives by creating panic in the financial markets. Freedom of the press and Reuter’s alleged mistake are furiously debated in the House of Commons until a message from the U.S. Embassy confirms that he has been right all the while. “Mr. Reuter, I offer you the apologies of Her Majesty’s government,” says the prime minister. “By your reliability and your veracity, you have saved the press from another of those countless attempts to take away its freedom!” Reuter’s vindication is matched by an exhilarating musical score to present the ultimate image of the journalist as hero.

A Dispatch from Reuters represented one of Hollywood’s responses to lobbying efforts from press associations for depictions of journalism as a champion of democracy rather than a servant to money and sleaze. The press associations had reason to worry—the image of journalism that had been presented in the media up until 1940 often had been less than benevolent.

Ehrlich-Saltzman, Heroes and Scoundrels: The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture – pages 23-24. ©University of Illinois Press, 2015

This chapter includes: History and Popular Culture, Early Modern Journalism and Popular Culture, "High Modern" Journalism and Popular Culture.

Other Resources:

19th Century Novels Featuring Journalists

Herodotus as an Ancient Journalist: Reimagining Antiquity's Historians and Journalists http://ijpc.uscannenberg.org/journal/index.php/ijpcjournal/article/view/22/29

Sweat Not Melodrama:http://ijpc.org/uploads/files/watergate.pdf

Good on journalism fiction:

http://ijpc.org/uploads/files/Howard%20Good%20The%20Journalist%20in%20Fiction%20Journalism%20Quarterly.pdf

Carrying the Banner: The Portrayal of the American Newsboy Myth in the Disney Musical, Newsies. http://ijpc.uscannenberg.org/journal/index.php/ijpcjournal/article/view/8/10

The landmark study, The Image of the Journalist in Silent Film, 1890 to 1929, Parts One and Two, containing 3,462 silent films with 21 appendices totaling more than 10,900 pages has been published in Volumes Seven and Eight of The IJPC Journal.

In Part One: 1890 to 1919, a total of 1,937 films, with each character and event identified and all of the table information encoded, were annotated and put into eleven appendices – Appendix 1, 1890-1909 (104 pages); Appendix 2, 1910 (83 pages); Appendix 3, 1911 (92 pages); Appendix 4,1912 (179 pages); Appendix 5, 1913 (280 pages); Appendix 6, 1914 (617 pages); Appendix 7, 1915 (771 pages); Appendix 8, 1916 (788 pages); Appendix 9, 1917 (764 pages); Appendix 10, 1918 (471 pages); Appendix 11, 1919 (478 pages). Many of the films include jpegs of original reviews, advertisements and photographs showing journalists in action.

In Part Two: 1920-1929, a total of 1,514 films with each character and event identified and all of the table information encoded, were annotated and put into ten more appendices -- Appendix 12, 1920 (753 pages); Appendix 13, 1921 (702 pages); Appendix 14, 1922 789 pages); Appendix 15, 1923 (689 pages); Appendix 16, 1924 (538 pages); Appendix 17, 1925 (605 pages); Appendix 18, 1926 (573 pages); Appendix 19, 1927 (573 pages); Appendix 20, 1928 (620 pages); Appendix 21, 1929 (576 pages). Many of the films include jpegs of original reviews, advertisements and photographs showing journalists in action. In the endnotes, future researchers can also find a complete list of films dealing with specific journalists, such as cub reporters, female reporters or pack journalists.

Check out the other chapters: